From RFK: His Words for Our Times:

On the Death of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr

Indianapolis, Indiana April 4, 1968

Kennedy launched his Indiana primary campaign on April 4, with a series of campus rallies. At Notre Dame, he had decried poverty, hunger, and joblessness. At Ball State University, he spoke of his belief in a generous America, and in the question-and-answer period that followed, a young black man asked, “You are placing great faith in white America. Is this faith justified?” Kennedy answered affirmatively and added, “I think the vast majority of white people want to do the decent thing.” Immediately before boarding the plane in Muncie to fly to Indianapolis, Kennedy received a call from Pierre Salinger (his brother’s press aide and a 1968 campaign adviser), who told him that Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot in Memphis.

Kennedy and his press secretary Frank Mankiewicz huddled on the short flight; they feared from the initial reports that King would not survive. Kennedy, still deeply scarred from his brother’s assassination, struggled to comprehend this latest shooting and to determine what he should say about it publicly.

On landing in Indianapolis, Kennedy learned that King was dead. His advance men, Walter Sheridan and (now Congressman) John Lewis, had scheduled a rally in the heart of the city’s ghetto, an event that Indianapolis Mayor Richard Lugar thought was too dangerous, even in the quieter times when the schedule was made.

The evening was chilly and raw. Lewis and Kennedy’s traveling aides learned that the ghetto was quiet—word of the assassination had not reached the neighborhood—but Indianapolis Chief of Police Winston Churchill advised Kennedy not to go because he expected there would be violence as soon as the news became known. Kennedy grimly decided to proceed as planned, and, having sent his pregnant wife ahead to the hotel, he rode to the site in silent contemplation.

When his car entered the black neighborhood, the police escort dropped off. The press bus became separated from the candidate, and on the bus Frank Mankiewicz frantically tried to draft a coherent statement from the images and concerns Kennedy had expressed on the plane.

About one thousand people were waiting, in a carefree mood typical of a rally. Walinsky, also having been separated from Kennedy when the motorcade was disbanded, rushed up with suggested talking points. Kennedy thanked him distantly, crumpled the notes, and jammed them into his overcoat without glancing at them.

Having specifically requested that he not be formally introduced, Kennedy climbed onto a flatbed truck that was serving as a platform. “He was up there,” said television correspondent Charles Quinn, “hunched in his black overcoat, his face gaunt and distressed and full of anguish.” The only illumination came from floodlights, bathing the truck platform. As Mankiewicz raced up, with his own legal-pad speech draft, he realized he’d never reach the candidate in time.

Speaking extemporaneously, Kennedy said, in a sad, tremulous voice:

I have bad news for you, for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world, and that is that Martin Luther King was shot and killed tonight.

A huge gasp came from the people and then screams of “No! No!” Kennedy somberly went on.

Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice for his fellow human beings, and he died because of that effort. In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black—considering the evidence there evidently is that there were white people who were responsible—you can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization—black people amongst black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another.

Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love.

For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.

My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He wrote: “In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.”

What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness; but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black.

So I shall ask you tonight to return home, to say a prayer for the family of Martin Luther King, that’s true, but more importantly to say a prayer for our own country, which all of us love—a prayer for understanding—and that compassion of which I spoke.

We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times; we’ve had difficult times in the past; we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence; it is not the end of lawlessness; it is not the end of disorder. But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings who abide in our land.

Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.

Let us dedicate ourselves to that, and say a prayer for our country and for our people.

Kennedy was a unique white public official in America able to address a crowd in a black neighborhood that tragic night and not encounter violence. He spoke as a recognized champion of the disadvantaged, and he carried the credibility of his family’s tragedy; in fact, this night marked the first time he had referred publicly to his brother’s shooting.

Whether Kennedy’s appearance was a factor—and it seemed surely to have been—Indianapolis remained quiet while rioting broke out in 110 cities across the land, causing thirty-nine deaths, twenty-six hundred injuries, and tens of millions of dollars of property damage.

Returning to his hotel, Kennedy phoned Coretta King, and then (at her request) asked Mankiewicz to make arrangements for the body of the slain civil rights leader to be flown from Memphis to King’s home in Atlanta. Carrier after carrier refused, anxious about the resulting notoriety, as the night of black rage continued to sweep across the nation. Finally, in the early morning hours, a private plane was borrowed from a Kennedy friend in Atlanta.

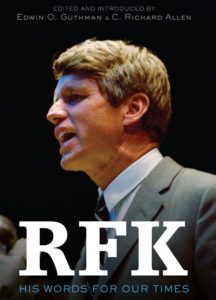

(Photo by Leroy Patton, AP (c) )